NØRDIC NEWS

light house on a common ground

Eldin Oscarsson photo by Magda di Siena

Magda di Siena is an architect, an interior stylist and an art consultant. Her work is focused on projecting and setting exhibitions, fair stands, paper advertisements. She visited the Venice Architecture Biennale and shares with us the Nordic Pavilion.

One of the most interesting pavilions at the 13th Venice Architecture Biennale is undoubtedly the Nordic pavilion (representing Norway, Finland and Sweden), built in a 1962 design by Sverre Fehn, which celebrates its 50th birthday this year. To mark the occasion the curator, Peter MacKeith, has commissioned 32 architects, all born after 1962, to present their concepts of architecture as common ground.

In this pavilion, whose interior includes a number of trees integral to Fehn’s design, the concept of an open dialogue with nature is already clearly expressed, and it seems that the new generations have taken the idea to heart. After meetings, workshops and discussions between the participants, the structure of the exhibition was mapped out clearly and effectively: the decision was to exhibit, in the form of installations (the supports for which were designed by Professor Juhani Pallasma, a colleague and friend of Fehn), conceptual elements that would lead the visitor to an immediate reflection on perceptions of space, materials to be used in construction and attention to the surrounding landscape: considerations which were for too long labelled ‘utopian’, but are now seen again as essential elements in any sustainable project of high aesthetic and functional quality.

Light house: on the Nordic common ground is the title chosen for the Scandinavian contribution to the Venetian exhibition. If architecture is once again a space for dialogue, what should it bring with it for this resumed journey? This is the question posed by the Biennale’s curator, David Chipperfield. The Scandinavian reply is the contents of Light house, which in a broad sense can also be taken as just (just?!) a collection of good ideas, good intentions, ‘cells’ from which new spatial and material conceptions can grow alongside a better constructional awareness.

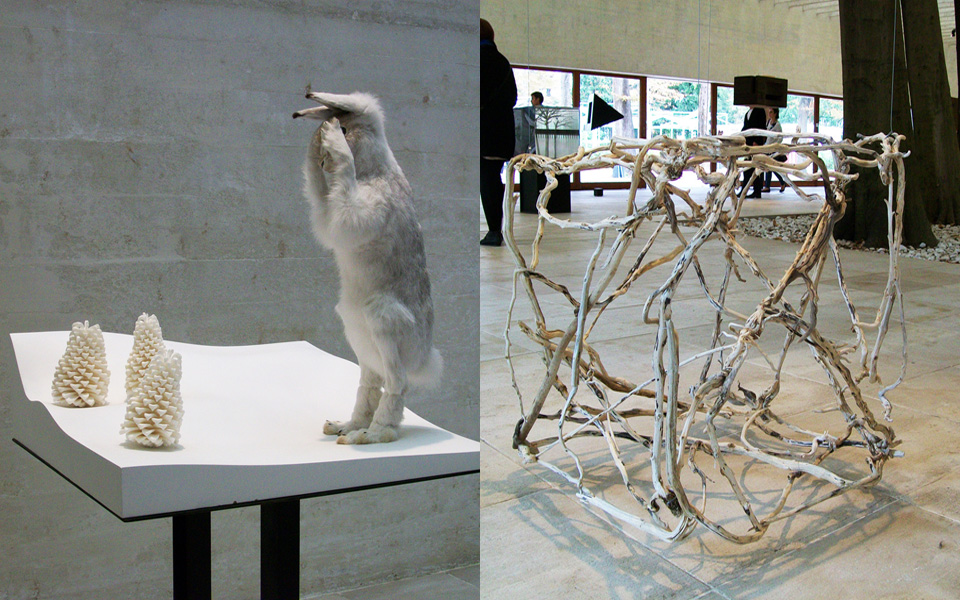

The visitor’s attention is seized at once by Adaptation, a work by the Haugen Zohar Arkitekter: a leveret covering its eyes with its forepaws in front of three pine cones painted white. Halfway between tragic and comic, this installation brings the observer face to face with an important question: is what we produce always pleasing or right for the user?

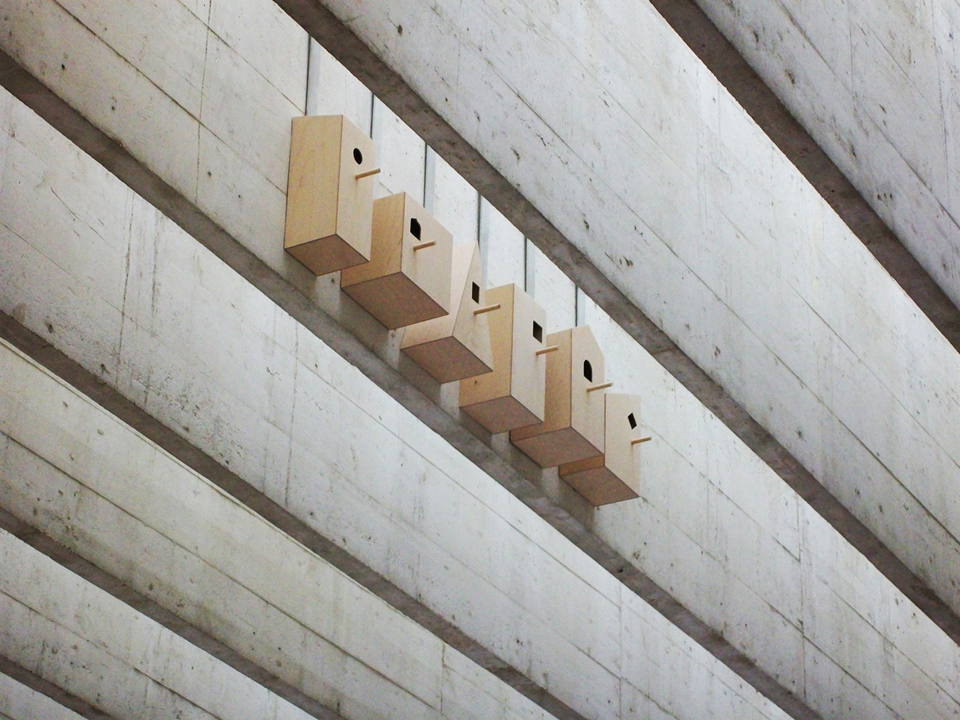

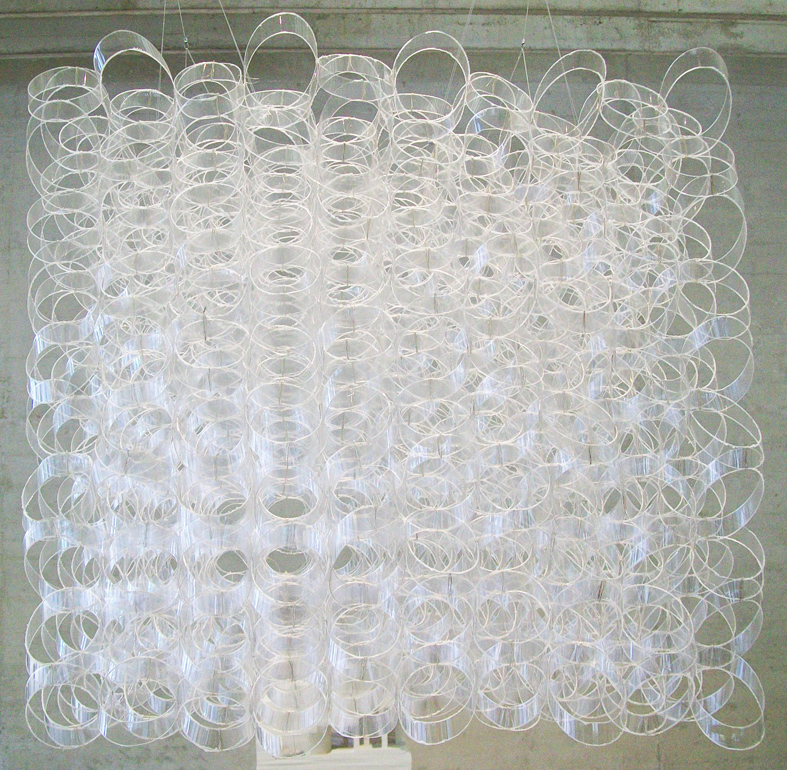

The territory we live in is, furthermore, shared with other species; they take part instinctively in a dialogue about building and we should pay attention to them before intervening on the territory. Another visually striking installation is the cube created by Marge Arkitekter out of rings cut from plastic bottles. This installation clearly defines the potentialities of materials designated as rubbish, which can and should be thought of as materials to be re-used in new processes with surprising new possibilities and new aesthetic qualities. Similar thoughts arise from the Hollmenn Reuter Sandman team’s structure of irregular branches bent into the shape of a cube.

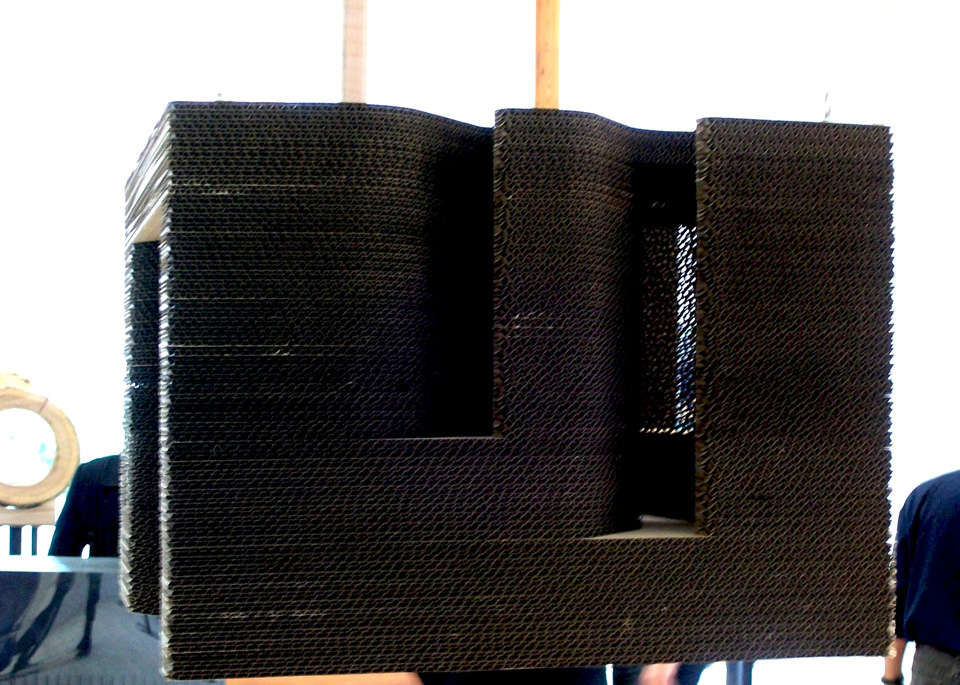

The imperfect has within it the potential to reveal new poetic forms, a tree can be transformed into something else without losing its identity. Likewise cardboard packaging can be transformed (by Verstas Architects) into an interesting model for the study of a living space. The idea of an architecture that refuses to impose itself forcefully, but almost camouflages itself in the territory of its insertion is well expressed by Tham & Videgards through a piece of stylised woodland in which a small house is placed almost as if it were its fruit. Manthey Kula also proposes a reflection on the re-utilisation of materials through a design for a seat created from scrap timber and a vertical element in grey felt, communicating a desire for non-formalisation, while managing to describe atmospheres and sensations even with poor materials.

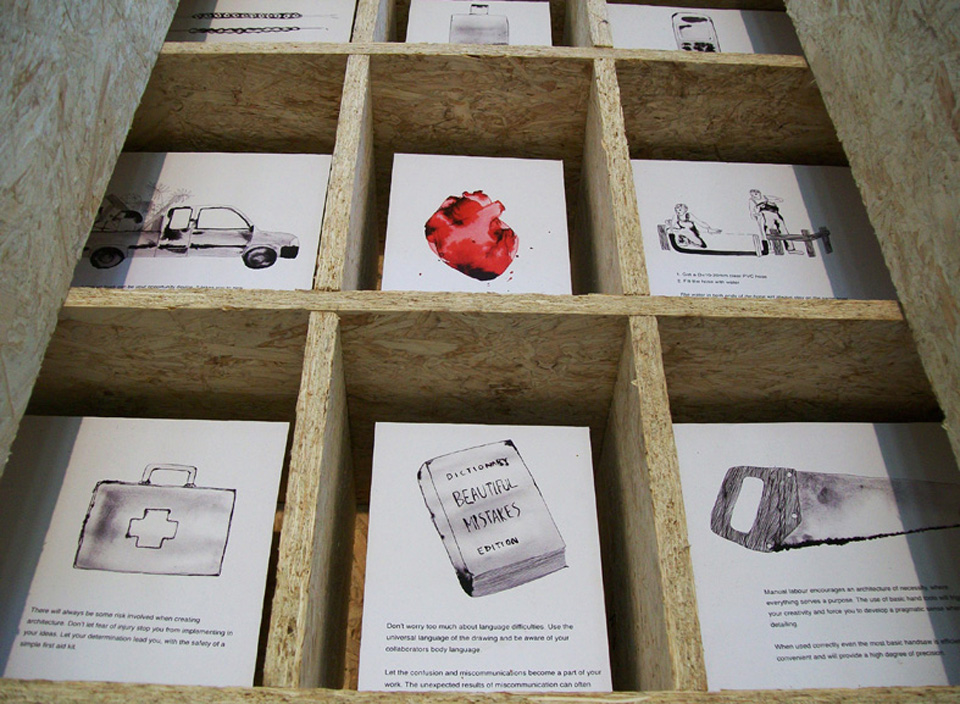

Closing this short tour, we might look at the installation by TYIN tegnesteu: a tool-box containing a collection of thoughts and maxims for working well and feeling good in the company of others. Among other ‘tools’ is a dictionary of beautiful mistakes, including this quotation: ‘Don’t worry too much about language difficulties. Use the universal language of the drawing and be aware of your collaborators’ body language’. A handy message to carry about in an ever more globalised world, where people of diverse languages and traditions are continually meeting on common ground.

Magda Di Siena

Marge Arkitecter photo by Magda di Viena

Left : detail of the pavilion - Right : Tham & Videgard - Photos by Magda di Viena

Manthey Kula photo by Magda di Siena

Left : Haugen Zohar Arkitekter - Right : Hollmen Reuter Sandman Architects _photos Magda di Siena

TYIN tegnestue photo Magda di Siena

TYIN tegnestue photo Magda di Siena

Verstas Architects photo Magda di Siena