SIMPLY SOUTH

scarred for life

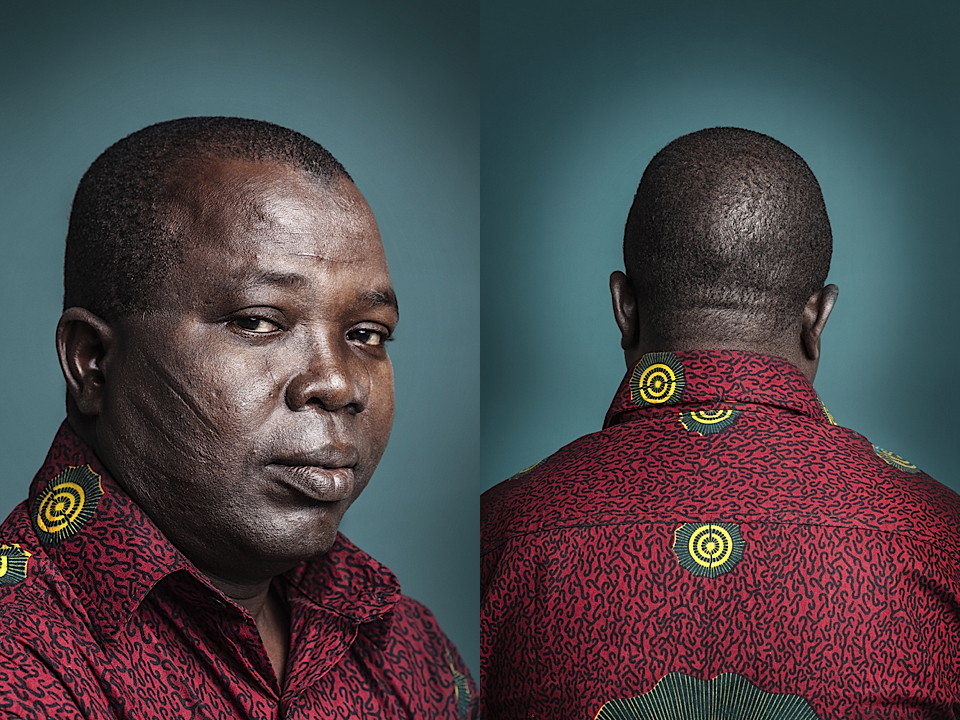

Photos by Joana Choumali

In Joana Choumali´s ”haabré, the last generation », questions of life experiences are being highlighted in a most interesting way. Choumali is a photographer born in 1974, currently based in Abidjan (Côte d’Ivoire). She studied Graphic Arts in Casablanca (Morocco) and has worked as an Art Director for McCann-Erickson, Abidjan, before embarking on career in photography. In « haabré, the last generation” she felt the need to document the last generation of people who have the body art phenomena scarifications as an expression of identity, showing both the controversy and the beauty of this traditional practice.

The reasons for getting scarifications, which is a superficial incision in the human skin, are diverse – hedonistic reasons in most parts of the world and storytelling in others. Haabré means writing in Kô language from Burkina Faso but could also stand for scarification. Social scarification, used to tell a story of tribe identity, is a tradition that has ancient origin in Africa and is a common practice in many regions on the continent. This especially in West Africa, where it replaced tattoos that show poorly on dark skin. It often takes form during a rite in which a person goes from being a child into adulthood.

Looking back even further through ancient history, patterns of scarification can be found in sculptures in Ife in South western Nigeria, which was, and still is today, the sacred city of the Yoruba people. When the city flourished artistically around the 10th century, it provided a tradition of naturalistic sculpturing with one of the findings showing a cast bronze head which is covered with thin, parallel scarification patterns that contrasts to the round features of the head. This head is believed to be a female Oni, which is a king or a ruler. Similar geometric patterns have also been used in architecture, found in farming communities on the border between Burkina Faso and Ghana. In those cases the patterns are used for wall decoration, where women paint the walls of round dwellings both inside and out with horizontally molded ridges called yidoor and long eye (long life) to express good wishes for the family. Like the sculpture of the Oni, the yidoor that consists of triangular patterns are spread over the wall in several rows. Pottery and baskets are also decorated in the same way. « When people decorate themselves, their homes, and their possessions with the same patterns, art serves to enhance cultural identity » (Stokstad & Cothren, 2011).

This is evident in different expressions, scarification being one of them, while in the western part of the globe commercial brands have become a signal of characterization, with the logo or brand name playing a significant semiotic role used to express who we are, making consumption an inevitable club where we go to practice ritual around identity.

”Haabre, the last generation” depicts men and women who have become representative of their communities through scarification. It is a practice forged around repetition, symmetry and texture as an art form.

Choumali’s work also has an anthropological value in the way that she is documenting a story that is heading for an end. The arrangement reflects this issue by using strong lightning to catch a moment of the subjects as they are. Speaking to us showing us both who they are and what their identity as a person is within a tribe context. The created patterns are a reminder of their culture, history and future, and they are meant to be worn proudly in the face of their skin, creating an abundance palette of texture, relief and landscape on the human body.

It is of course a subject beyond esthetic wonders – yet don’t we all bear a scar of some sort? Scars of age, scars of war and scars of life. It is true that some people would like to get rid of their scars because of the abnormality of the esthetic in today’s society, which for some people has an impact on their feeling of pride. Being a tradition of intimate nature, the scars can cause a conflict of difference due to urbanization.

« I remember Mr. Ekra , the driver who took me to school. Ekra had large scars that marked his face from temple to chin. I found these fascinating geometric shapes, and normal at the same time. Ivorian from the east-center of the country, Ekra was not an exception. It was common to see people with various scars proudly displaying their social origins. I remember a famous minister of ‘Information ‘, originally from northern Côte d’Ivoire, and a noted pilot commander, who also wore scarifications, and it appeared to us as banal. The years pass, and the practice gradually disappears.” – Choumali.

Text: Rosewood Magazine, Joana Choumali

Photos: Joana Choumali

http://joana-choumali

We are happy to share with you this post originally published on Rosewood Magazine, a proud narrator of stories that matter, connecting singular subjects to a global audience. This young magazine focus on creativity on the African continent and trends in general.

www.projectrosewood.com

Photos by Joana Choumali

Photos by Joana Choumali

Photos by Joana Choumali

Photos by Joana Choumali

Photos by Joana Choumali

Photos by Joana Choumali

Photos by Joana Choumali

Photos by Joana Choumali